The challenge of inclusive dialogic teaching in public secondary school

Abstract

The challenge of creating more inclusive public schools addressing the needs of the 21st century Knowledge Society is a major one. In this paper, we focus on inclusion as a dialogical process to be adopted and developed by teachers and students alike in any classroom. The idea of inclusive dialogic teaching is explained and operationalised in an inclusive dialogic curriculum focusing on cultural literacy learning dispositions. In this study, which is part of a multi-country European project, eight Spanish and Portuguese secondary school teachers and their students participated in eight sessions performing dialogic lesson plans. Teachers attended two professional development sessions, one at the beginning of the project and another one later on. Classroom discourse data from sessions #3 and #8 were collected and analyzed using a pre-constructed coding scheme. The findings show a slight improvement in dialogicity from session #3 to session #8 with a persisting resistance from teachers to be more cumulative in their discourse. These findings confirm previous work showing that dialogic teaching is acquired gradually, and even when there are changes in teachers’ stance being more inclusive and inviting towards students, these changes do not necessarily represent a radical shift in the teaching methods towards being more student-centered.

Keywords

Dialogic teaching, inclusive education, secondary school, teaching practice, teaching professional development, dialogue

Palabras clave

Enseñanza dialógica, educación inclusiva, escuela secundaria, práctica docente, desarrollo profesional docente, diálogo

Resumen

El reto de promover escuelas públicas más inclusivas que aborden las necesidades de la Sociedad del Conocimiento del siglo XXI es importante. En este artículo nos centramos en la inclusión como un proceso de diálogo que tanto docentes como estudiantes deben adoptar y desarrollar por igual en las aulas. La idea de la enseñanza dialógica inclusiva se explica y operacionaliza en un currículo dialógico inclusivo centrado en las disposiciones de alfabetización cultural. En este estudio, que forma parte de un proyecto europeo de varios países, ocho docentes de secundaria españoles y portugueses y sus estudiantes participaron en ocho sesiones que implementan planes de lecciones dialógicas. El profesorado asistió a dos sesiones de desarrollo profesional, una al comienzo del proyecto y otra más adelante. Los datos del discurso en el aula de las sesiones n.º 3 y n.º 8 se recopilaron y analizaron utilizando un protocolo de codificación validado. Los resultados muestran una ligera mejora en la dialogicidad de la sesión n.º 3 a la sesión n.º 8 con una resistencia persistente de los docentes para ser más acumulativos en su discurso. Estos hallazgos confirman el trabajo previo que muestra que la enseñanza dialógica se desarrolla gradualmente e incluso cuando la postura del profesorado pasa a ser más inclusiva y atractiva para el alumnado, este cambio no representa necesariamente un cambio radical en los métodos de enseñanza centrados en el alumnado.

Keywords

Dialogic teaching, inclusive education, secondary school, teaching practice, teaching professional development, dialogue

Palabras clave

Enseñanza dialógica, educación inclusiva, escuela secundaria, práctica docente, desarrollo profesional docente, diálogo

Introduction

The challenge of creating more inclusive public schools addressing the needs of the 21st century Knowledge Society is a major one. Extensive work has been reported regarding the promotion of social inclusion policies in education mainly in two directions: a) Towards the inclusion of “objectively” excluded populations such as immigrants, low-income, and socially, mentally or physically disadvantaged students (Camilli-Trujillo & Römer-Pieretti, 2017; Castillo-Rodríguez & Garro-Gil, 2015); b) Towards the inclusion of “subjectively” excluded populations in aspects such as media, digital or critical literacy skills (Dias-Fonseca & Potter, 2016) (for the distinction between objective and subjective inclusion see Licsandru & Cui, 2018). However, inclusion does not only regard specific groups of learners and their limited access to material or non-material resources, including knowledge and skills; recent efforts of public schools towards a more inclusive education tend to focus on the classroom climate and the fostering of “learning for all” opportunities, for example through whole-class dialogue (Mitchell & Sutherland, 2020).

Dialogic teaching can be broadly defined as an approach for “teaching and learning through, for and as dialogue” (Kim & Wilkinson, 2019: 70). Although there are different approaches to dialogic teaching (Asterhan et al., 2020; Kim & Wilkinson, 2019), authors agree on the following aspects: 1) Dialogic teaching must be intentional (Bakker et al., 2015; Reznitskaya, 2012); 2) Learnt (Fisher, 2007; Simpson, 2016); 3) Assessable (Lehesvuori et al., 2011) as per its adherence to principles and routine practices with a dialogic quality (Alexander, 2017). Students’ agency, manifested in them acting “authoritatively and accountably (problematizing and solving issues)” (Kumpulainen & Lipponen, 2010: 50) is the other necessary side for dialogic teaching to emerge in a successful way. The role of teachers in allowing and fostering productive and constructive dialogue is essential in this regard (Reznitskaya & Gregory, 2013; Sedova et al., 2016).

Several scholars have argued that dialogic teaching is difficult and gradual to develop (Clarke et al., 2016; Reznitskaya & Wilkinson, 2015; Sedova, 2017; Wilkinson et al., 2017). Such difficulty is even greater when it comes to teachers orchestrating whole-class discussions (Clarke et al., 2016; Sedova et al., 2016), and it is mainly related to the effective facilitation and mediation of students’ contributions with the aim of reinforcing their own participation and accountability (Michaels et al., 2008). For instance, it has been observed that even when teachers become able to open genuine dialogical discussions with at least three students participating in those for at least 30 seconds (Sedova et al., 2016), teachers’ and students’ capacity to refer back to the discussion contents in ways that incentivise genuine contribution of ideas by the same or different students remains limited (Lehesvuori et al., 2013; Sedova et al., 2014). This capacity refers to the concept of ‘cumulativity’ of discourse introduced by Alexander (2017), which forms one of the main principles of dialogic teaching, together with: ‘purposefulness’ (i.e. teachers planning and steering classroom talk with specific educational goals in mind), ‘collectiveness’ (i.e. teachers and children addressing learning tasks together), ‘reciprocity’ (i.e. teachers and children listening to each other, sharing ideas and considering alternatives), and ‘supportiveness’ (i.e. students expressing their ideas freely without the fear of wrong answers and helping each other to reach common understandings).

The present study is part of a multi-country, cross-sectional (pre-primary, primary and secondary) large-scale intervention project focusing on the acquisition of dialogic teaching practices and implementation with the goal of fostering cultural literacy learning skills among students. As part of this project, cultural literacy was defined as a dynamic set of dispositions, resulting from social, dialogical practice which leads the individuals to an empathetic, tolerant and inclusive acceptance of “the other” (Maine et al., 2019). This study focuses on inclusion as a teacher’s disposition towards students, as manifested in inclusive dialogic teaching talk moves resulting in more or less dialogic student moves in Portuguese and Spanish secondary classrooms.

Literature review

Inclusion as a value in education

Between 1970 and 1990 mainly, the European Union promoted the idea of social inclusion and, since then, it is an established concept in European politics (Wright & Stickley, 2013). The literature about inclusion is extensive and covers a wide range of areas, such as social, political, organisational, educational or health; and issues, such as poverty, multiculturalism, inclusive education, people with disabilities and/or mental illness. In educational contexts, there are several studies about inclusive education and integration of children and youth with special educational needs (Castillo-Rodríguez & Garro-Gil, 2015; Woodcock & Woolfson, 2019). In health, several publications on mental illness and social inclusion and exclusion are available (Davey & Gordon, 2017), and in organisational contexts inclusion also emerges as a concern or as an aim (Schmidt et al., 2016). In education, inclusion is defined not only as an active process of change or integration, but also as a result, such as the sense of belonging (Osler & Starkey, 1999). This view is shared by Freire (2008), who describes inclusion as an educational, political and social movement that defends the right of all individuals to consciously and responsibly participate in society and to be accepted and respected in what differentiates them from others. According to the author, inclusion is based on values such as respect and celebration of differences, and collaboration between individuals, social groups and institutions. This view on inclusion, also adopted in the present study, goes beyond individual differences in terms of special education needs (which is better defined as “integration” rather than inclusion, see (Castillo-Rodríguez & Garro-Gil, 2015), and addresses all individuals and their efforts to participate in social dialogue fostering collaboration. To facilitate collaboration, individuals should value diversity, respect others, and demonstrate an interest in overcoming their prejudices and reaching compromise solutions (European Union, 2006). The main goal of inclusion is that no culture -in its broad sense, i.e. not limited to ethnicity- overlaps or imposes itself on another (Seeland et al., 2009; Vázquez, 2001). According to Tienda (2013), in order to promote inclusion and increase tolerance, it is necessary that individuals from different backgrounds (geographical, religious, political, social, etc.) interact in such a way that challenges pre-existing stereotypes.

Inclusive dialogic teaching

Inclusive dialogic teaching is about the promotion of a social or inclusive dialogic pedagogy that goes beyond knowledge transmission (Osborne, 2007; Simpson, 2016). Reporting the outcomes of their UK-based project titled “Classroom talk, social disadvantage and educational attainment: raising standards, closing the gap”, Alexander et al. (2017) mention that students’ preparedness to listen to others improved, and their interaction became more inclusive, with fewer students being isolated, silent or reluctant to participate. Moreover, “with an increased emphasis on a supportive, reciprocal talk culture, pupils gained in confidence and became more patient and better attuned to each other’s situations and keen to provide mutual support in both talking and learning” (Alexander et al., 2017: 6). Similar results were obtained by the “Schooling for a Fair Go” project in Australia (Vass, 2018). For those teachers, dialogic teaching was a “transformative journey towards engaging classroom practices” (Vass, 2018: 109), and this transformation included both teachers and students. As one of the Australian teachers described, her participation in the dialogic teaching project was like a rainbow to take a journey over, for both her students and herself. Similarly, in a dialogic teaching project in Finland (Kumpulainen & Rajala, 2017) called “The Forest Project”, the analysis of classroom discourse data showed how important it was that teachers managed to identify and negotiate students’ diverse discursive identities within productive interactions in science.

In general, teachers’ adoption of a dialogic stance has shown to help students develop their own meaning-making processes and disposition towards “a dialogic how, a personally engaging what, and an inclusive whose” (Boyd, 2016: 3). As part of this active dialogic stance allowing space for students’ participation and agency, teachers are called to also adopt a facilitative stance (Blanton & Stylianou, 2014), i.e. implementing specific talk moves or dialogue prompts to structure or orient interaction towards more productive and constructive directions. Finally, as part of this facilitation, teachers are also encouraged to show a critical stance (Fisher, 2007; Haneda et al., 2017), i.e. enacting a critical thinking attitude towards students’ claims and their justifications, asking them questions like “how do you know?” or even challenging their viewpoints opening up the dialogue space for constructive disagreement. Inclusion as a dialogic teaching approach is present in the three stances described above: an inclusive dialogic stance is the one that allows egalitarian participation and agency. An inclusive facilitative stance is the one that fosters interaction among students, even in a whole-class discussion format; and an inclusive critical stance is the one proving that for someone to be able to evaluate what others say, and how it is different from what (s)he says, (s)he first needs to truly understand what the alternatives to one’s own viewpoint are. In other words, for authentic dialogue and argumentation to emerge in the classroom, an attitude of openness towards “otherness” (Wegerif, 2010) is an essential ingredient of both the teacher’s and students’ discursive behavior.

Overall, although inclusion has been largely described as an education policy and practice goal, its framing as an integrated part of teachers’ stance and subsequently classroom discourse has not received much attention. This is the gap that this study aims to address.

Methodology

Research goal and context

The study’s goal was twofold: first, to identify whether inclusive dialogic teaching is a suitable method at secondary school, given that most studies focus on primary school teachers; and second, to explore whether and how the practice of dialogic teaching in time leads to more/different inclusive dialogic classroom practices. According to these goals, our guiding research questions are:

-

RQ1: Does professional development designed to promote dialogic teaching have an effect on teachers’ and students’ degree of dialogicity?

-

RQ2: Which are the most common talk moves manifested by teachers and students throughout the dialogic lessons?

Within the cultural literacy learning program developed as part of this project, dialogue and constructive argumentation were conceived as the basis for fostering an inclusive dialogic stance from both teachers and students. The classroom was conceived as a safe environment where students could express themselves without being judged and where all ideas were accepted as valid. In order to work towards this dialogic ethos, the development of “ground rules for talk” (Littleton & Mercer, 2013) were included as part of the program. This activity involves teachers with their students establishing rules on how they should interact. Some examples of rules may include: “Everyone contributes to the discussion”, “All ideas are respected and considered” and so on. Each dialogic lesson was structured upon a cultural literacy multimodal text, which was either a wordless picture book or a wordless, animated short film promoting the values of inclusion, tolerance and empathy and their inter-connected values and dispositions such as social responsibility, active participation or sustainable development.

As part of their professional development, the participant teachers were guided through 15 pre-constructed lesson plans, for which inclusive dialogic teaching was a central part. All lesson plans had primary and secondary questions that the teacher could ask to guide whole-class discussion, as well as concrete dialogic and argumentative small-group activities to follow up that discussion. Among the techniques that became available to teachers to use as part of their whole-class discussions were: talking points (https://bit.ly/32hjuIe), thought-provoking questions (https://bit.ly/2AXcOnj), and circle of viewpoints (https://bit.ly/3j2IMzV). One of the innovative aspects of the dialogic curriculum we developed as part of this project was the fact that several dialogic teaching techniques were used both from the dialogue and argumentation research fields. Moreover, these techniques were integrated as part of pre-constructed lesson plans in which an attractive and open to several interpretations cultural text (either a book or a film) was the main object of discussion. Finally, it is also noteworthy that the 45 total lesson plans, 15 for each age group, were constructed together with volunteering teachers in co-design sessions in a piloting phase prior to the implementation of the program. In this way, the teachers’ voice and expertise with the specific age groups were reflected in the lesson plans.

Participants

Eight secondary teachers (four Spanish and four Portuguese) and their students participated in the study reported here. All teachers and their students signed corresponding consent forms at the beginning of the project confirming their voluntary participation and right to withdraw from the project at any moment. In the case of the students, informed consents were signed by their parents/caregivers. Table 1 presents a basic description of the participants.

Design and data collection

We carried out an instructional design study, based on observational methodology. Although the project was planned for three phases, the Covid-19 lockdown affected its full implementation. In this paper, we analyse data concerning the actual data collection which comprises phases 1 and 2. A total of eight sessions were implemented by each teacher. Altogether 16 sessions were video-recorded, corresponding to two sessions per class. Professional development sessions took place twice, at the beginning of the program and before session #6. According to the original project, only session #3 and session #8 were considered for data collection. Figure 1 depicts the chronological development.

Analysis

All classroom discursive activity in sessions #3 and #8 was transcribed and coded according to the Low Inference Discourse Observation (LIDO) tool (O’Connor & LaRusso, 2014).

The LIDO coding scheme provides ordinal categories for the teacher (from 1 to 6): (T1) Encouraging students to react to their classmates’ contributions; (T2) prompting and following up to deepen contribution; (T3) active listening to keep interaction; (T4) posing open questions; (T5) posing semi-open questions; (T6) posing single-answer questions.

The same scheme captures the student’s discursive action (from 1 to 5): (S1) Direct classmates’ interpellation; (S2) indirect reference to a classmate’s previous intervention; (S3) argumentative claim; (S4) elaborated utterance presenting full ideas; (S5) minimal utterance response (up to simple clause). All these categories indicate the degree of dialogicity in the classroom discourse. Categories T1, T2, and T3 describing teacher moves and S1, S2, and S3 describing student moves are considered as more dialogical than the T4, T5, and T6, and S4 and S5, correspondingly. The inter-rater reliability among four trained coders was calculated, reaching a satisfying result (Krippendorf’s α=0.77), and any discrepancies among the coders were resolved through discussions until final full agreement.

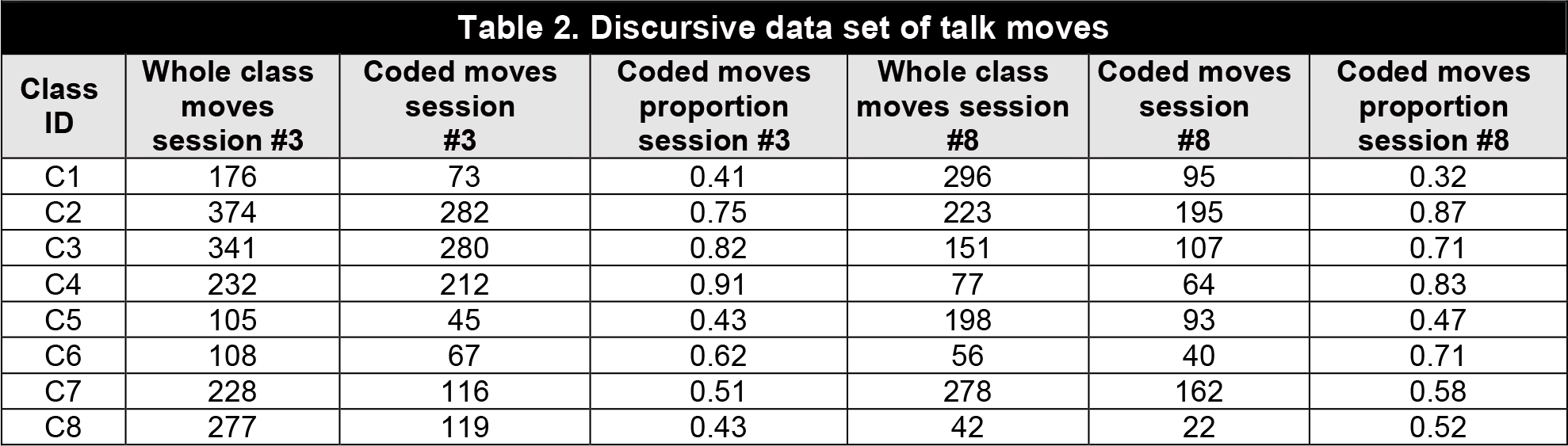

Table 2 shows the total number of talk moves, selected and coded per each class (the analysis only focused on the whole-class discussions and the coding excluded utterances that did not represent any dialogue moves according to the LIDO’s categories).

Results

The Findings section is structured into two parts. In the first part we present the distribution of the proportions of LIDO’s categories for teachers and students, respectively (see Table 3 and Table 4), as well as the means’ comparison between the two sessions in line with our first research question. In the second part, we focus on the type of categories emerged throughout the sessions in line with our second research question.

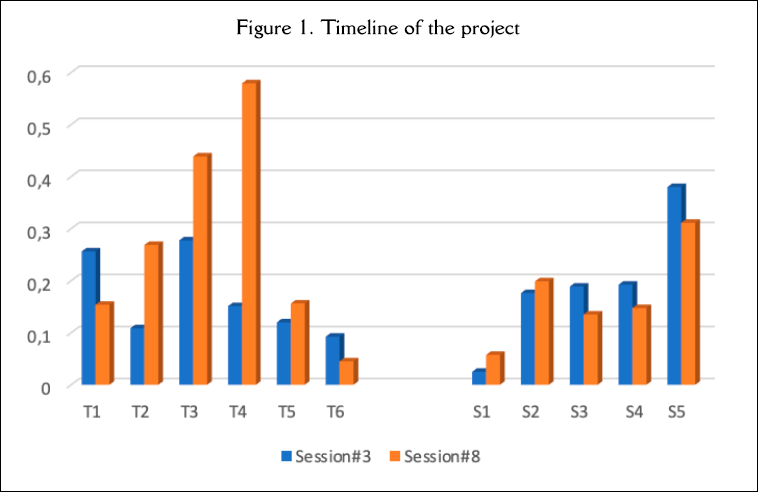

To reply to RQ1, we conducted a paired-samples non-parametric test (Wilcoxon) for each category comparing proportions for sessions #3 and #8. We can observe the Mean proportions in Figure 2. The Wilcoxon non-parametric test comparison of teachers’ and students’ talk moves across session #3 and session #8 yielded significant results only for one category for teachers (T4, Z=2.4, p=.018) and none for students.

In order to test whether this statistical difference was an isolated finding or not, we also compared the three most dialogic categories for teachers (namely T1, T2, and T3) between session #3 and session #8. The Mean (Standard Deviation) for the categories T1, T2 and T3 for session #3 was 18.5 (6.6) and for session #8 it was 27.6 (9.4).

The non-parametric Wilcoxon comparison test yielded significant results (Z=-1.8; p one-tail=.05), therefore confirming a potential progress in teachers’ dialogicity in time. We should note, however, a slight decrease in the Mean proportion of T1 (Figure 2), which can be explained by a slight increase in the Mean proportion of S1 (Figure 2).

To reply to RQ2, we looked at the type of teacher and student talk moves emerged in both sessions, with illustrating examples for each from our bilingual (Spanish and Portuguese) dataset. For the teachers’ categories, the overall (both sessions #3 and #8) frequencies were: T1=43, T2=87, T3=311, T4=116, T5=129, and T6=92. Correspondingly, the total frequencies for the students’ categories were: S1=46, S2=209, S3=174, S4=153, and S5=142. We can see that across the two sessions observed, the most common talk move among teachers was T3 (Active listening to keep interaction), which was mostly replied to with a minimal response by students (S5), also the most frequently used move by the students in our dataset. Among the students’ categories, the second most frequent move after S5 was S2 (Student refers to another student’s contribution), a much higher dialogical move. Although the statistical analysis did not yield differences across sessions, we observed changes in the frequencies of students’ moves from session #3 to session #8 (Figure 2). The low dialogical S5 move decreased, while the high dialogical S2 increased.

From a qualitative point of view, we observed that teachers tended to use a mainly teacher-centered discussion with a “radial” pattern of discourse, rather than a student-driven discussion. This pattern, predominant in session #3, could be described as: Teacher-Student A-Teacher-Student B-Teacher-Student C, etc. However, we observed a weak tendency towards a less radial and more homogeneously distributed discourse pattern in the subsequent session #8, which could be described as follows: Teacher-Student A-Student B-Student C-Teacher. Moreover, in this latter pattern, more dialogic teacher categories emerged (i.e., T1, T2 and T3). Below, we present two excerpts from the same class to illustrate the difference in the whole class discourse pattern between session #3 and session #8.

Excerpt 1. Example of a radial teacher centered discourse, in session #3:

-

Teacher: You should keep taking notes with the ideas so you could use them later. This one could be the first idea. Have you seen any change? You’ve seen a change, haven’t you? (T5)

-

Student A: Pollution (S5)

-

Teacher: Pollution. OK, at the top, at the bottom, everywhere? (T2)

-

Student B: Everywhere (S5)

-

Teacher: Have you seen any change since the beginning of the book? (T6)

-

Student C: Yes, the house gets bigger and bigger (S4)

-

Teacher: Bigger and bigger? (T3)

-

Student A: And grayer. (S5)

-

Teacher: Grayer? Caused by what? (T3)

In the low dialogical Excerpt 1, it is as if the teacher needed to limit the students’ opportunities to engage in dialogue, not to risk losing control of the conversation. Generally, in session #3, all teachers in our sample did most of the talking and led the discussion by minimizing the amount of talk from students. In contrast, in the subsequent session #8, teachers allowed more space for students to interact not only with them but also among themselves. The excerpt below shows a quite different discourse pattern, much less radial, in which the teacher allows space for students’ reacting to each other’s viewpoints, therefore contributing authentically and “accountably” (Kumpulainen & Lipponen, 2010) to the joint discourse.

Excerpt 2. Example of a student-centered discourse pattern, in session #8:

-

Teacher: You know all the rules of dialectical conversations, don't you? Basically, all options, opinions have to be respected and they have to be argued, okay? What do you think the meaning of the film is? (T5)

-

Student A: I think that it is like a representation of many people going to work away from home and working in a job that they may like but being a long time alone and away from home and excluded. This is why he seems sad. (S3)

-

Teacher: Very good, very interesting. Does the other group agree? (T1)

-

Student B: We think that... well... it's a person or whatever works on the moon turning it on and off every day so it's day and night and... of course it's alone and through music he feels better and expresses his feelings. (S3)

-

Teacher: What makes you think that he is sad and melancholic? (T2)

-

Student A: He was playing sad songs with his trumpet. (S4)

-

Student C: Also, he is crying and he misses home (S2)

-

Student A: Well, not only in that moment, his life is sad, he wakes up and does not smile at all. It is very dark, no lights, nothing happens (S3)

-

Student D: And boring (S2)

-

Teacher: Very good! So, what makes a house be a home? (T4)

In this second excerpt, we can observe some teacher moves that showed efforts to elicit elaborated reasoning from students. When we compare session #3 with session #8, we can observe that teachers are beginning to use discourse strategies in line with the dialogic teaching professional development, i.e. focusing on both dialogicity and cumulativity of joint discourse.

Discussion

Focusing on inclusion as a classroom dialogic practice in European public schools, our study showed that teachers gradually improved inclusive talk moves, such as the open questions and active listening, throughout their engagement in a dialogic teaching program explicitly aiming at students’ development of cultural literacy dispositions. This trend of progress across sessions towards a more dialogical classroom discourse can be explained by the nature of the dialogic curriculum in which dialogue and argumentation goals were explicit learning outcomes of each lesson plan. As Sandoval et al. (2018) argue, for teachers to reorganise their discursive practices into more dialogical ones, a well-structured professional development (PD) with clear instructions of lesson plans is necessary. Our PD lasted for 18 hours, and the lesson plans were carefully and explicitly designed and shared, which was probably the reason of the progress observed. Therefore, we can conclude that with a well-structured, lesson-plan-oriented PD, dialogic teaching in secondary schools is possible even in a short time and with no previous experience necessary. These results contribute to the current discussion about whether dialogic teaching and learning is an easy practice to acquire, and they offer optimistic insights when it comes to the effectiveness of a relatively short teacher PD for the fulfilment of concrete objectives (in our case, the implementation of pre-constructed lesson plans). Other studies with secondary school teachers following PD programs with a general focus on dialogic teaching principles without the concrete frame of lesson sequences constructed for that scope yielded some positive findings only after a considerable amount of time (e.g. at the end of one year in Sedova et al., 2016, and in Wilkinson et al., 2017, the PD lasted 30 hours).

Nonetheless, the observed improvement in teachers’ inclusive talk moves was not generalized nor for the totality of the moves, neither for students’ moves towards each other. This non-significant increase of more dialogical categories when it comes to both teachers and students is confirmed by previous studies that mention that the emergence of cumulative discourse, i.e. discourse building on previous contributions, is a difficult practice to achieve (Alexander, 2017; Lehesvuori et al., 2013; Sedova et al., 2016).

Along with those findings, some important considerations also need to be made. A first one has to do with the relatively small sample of the study (eight classrooms) and the exclusive focus on dialogue data. Our future research will focus on a multi-country corpus of approximately 200 classrooms who have participated thus far in the project, along with evaluation survey data from both teachers and students. A second important consideration is related to the impossibility of confirming any further dialogic teaching improvement at a later phase of the program, as it was initially planned but cancelled due to the Covid-19 lockdown. All participant teachers received a third PD before the session #11 of the program, the benefits of which will remain unknown. Part of our future work will consist in following those teachers in their new classes of the next year to see whether some of the learned dialogic teaching routines will be transferred to a different context without the support of a dialogic lesson plan. Based on other studies (Sedova et al. 2016; Wilkinson et al., 2017) our hypothesis is that for such transfer to be possible, and therefore for dialogic teaching learning to be sustainable, a deep shift in teachers’ epistemological beliefs regarding teaching and learning is necessary. The instruction provided in this study based on the implementation of dialogic lesson plans can be considered as effective for the purposes of the program, as students improved in their consideration of others’ in their own discourse, but maybe less effective in terms of the development of a dialogical, facilitatory, and critical stance from part of the teachers in the long term. In addition to that, there is always the risk of proceduralization of learning (Bereiter, 2002), mainly for the teachers, in the sense that they can apply the dialogical routines described in the pre-constructed lesson plans without a deep understanding of the principles and goals behind them.

Conclusion

When it comes to inclusion as both a goal and an outcome of dialogue in the classroom, our study shows that the more teachers become inclusive in their discourse, the more students imitate this strategy with their classmates. The fact that the lesson plans that formed part of our dialogic teaching program explicitly used inclusion, empathy, and tolerance as their learning goals certainly played a role in that. Instead of students being told that they would learn certain concepts related to history, physics or mathematics, they were told that the class was about listening to each other, exploring alternatives, or reaching consensus. Gradually, students became aware that learning how to live together with others is something that must be learned, and they dedicated part of their ordinary curriculum for that purpose. It is also relevant to mention that the program received a highly positive reception from the students, and cultural literacy dispositions became part of their everyday language. In a newspaper article about the project’s implementation in Portugal, low secondary school students who participated in the project said that “it doesn’t matter if you are right or wrong because everyone has a right to say what (s)he thinks” (Viana, 2020: 14). In nowadays’ society, when everyday becomes more vulnerable and uncertain, giving space to young people’s voices can be a catalyst for change and progress.

To conclude, the dialogic teaching practices observed in this study as result of teachers’ and students’ engagement in a dialogic curriculum focusing on inclusion, empathy and tolerance cannot be considered yet as full shifts towards a more dialogic, inclusive classroom. They are, however, as Sedova et al. (2014) first proposed, “embryonic forms” which certainly can mark a positive direction towards authentic dialogue and inclusive participation. A view of inclusion as a classroom dialogic practice needs to be further considered, also in line with extensive existing research in the field of adaptive and inclusive education (Mitchell & Sutherland, 2020). (1)